VR and Architecture: The Future of Immersive Design

Discover how Virtual Reality is transforming architecture. Explore top tools, immersive client presentations, and the future of design.

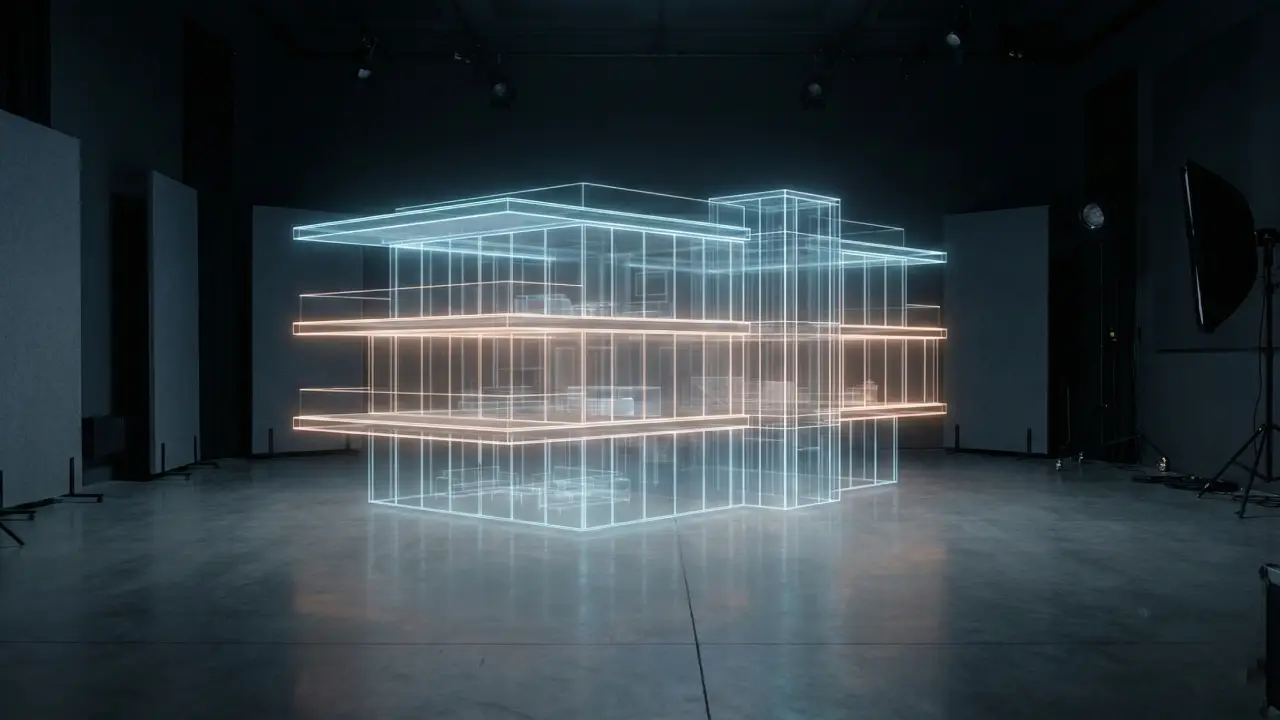

Imagine standing in the center of a cathedral of light. You can feel the vastness of the space above you, the weight of the stone columns, and the way the afternoon sun filters through the stained glass, casting dancing patterns on the floor. You reach out to touch the rough texture of the wall, and you can almost smell the dust and incense. Now, imagine that this cathedral does not exist. It is a ghost, a figment of data, a construct of geometry and light existing solely on a silicon chip. Yet, your brain—that ancient interpreter of reality—tells you that you are there.

For centuries, we architects have been in the business of translation. We take the three-dimensional dreams that live in our minds—constructs of volume, flow, and atmosphere—and we flatten them. We crush them into two-dimensional drawings, floor plans, sections, and static renderings. We hand these abstractions to clients and hope that they can decode the cipher, that they can rebuild the cathedral in their own minds using only these flat instructions. It is a process fraught with loss. The emotional resonance of a space, the intuitive flow of a corridor, the oppressive weight of a low ceiling—these nuances are often lost in translation.

But we are living through a fundamental shift in the history of our profession. The integration of VR and architecture is not just a new tool; it is a new medium. We are moving from the era of representation to the era of habitation. We no longer have to ask our clients to imagine; we can ask them to step inside. This technology allows us to inhabit the unbuilt, to test our assumptions against the rigor of human perception, and to sell a vision with a visceral power that no watercolor or ray-traced image could ever hope to match.

This report is written for you—the architect, the designer, the visualization specialist—who stands at this precipice. We will not just skim the surface of “cool tech.” We are going to dive deep into the machinery of this revolution. We will explore the psychology of virtual space, dissect the software ecosystems warring for your subscription dollars, analyze the hardware that powers these experiences, and, perhaps most importantly, talk about the business of VR—how to charge for it, how to use it to win work, and how to protect your bottom line. Welcome to the future of the built environment.

The Evolution of Spatial Representation

To truly understand where we are going, we have to respect where we came from. The history of architecture is, in many ways, the history of communication. When the master builders of the Gothic era designed their structures, they did not rely on the complex set of construction documents we use today. They used physical models, templates, and verbal instructions. The Renaissance brought us the codification of perspective—a mathematical way to trick the eye into seeing depth on a flat surface. This was revolutionary. Suddenly, a client could look at a drawing and see the building “as it would appear.”

Fast forward to the digital revolution. The transition from hand drafting to Computer-Aided Design (CAD) increased our precision but didn’t fundamentally change the output; we were still printing lines on paper. Then came 3D modeling and Building Information Modeling (BIM). We began to build “virtual buildings” rich with data. We could slice them, render them, and analyze them. Yet, the interface remained a 2D screen. We were peering into a digital aquarium, observing the fish from the outside.

VR and architecture smash the glass of that aquarium. This shift is driven by the concept of “presence.” Presence is the psychological state where the user behaves and feels as if they are in the virtual world, even though they know they are not. It is the “magic” that expert visualization specialists refer to. When you achieve presence, the brain switches from an analytical mode (“I am looking at a picture of a room”) to an experiential mode (“I am in a room”). This triggers physiological responses: a raised heart rate when looking over a virtual balcony, a sense of calm in a well-lit virtual atrium, or distinct discomfort in a cramped virtual hallway.

This evolution is not merely aesthetic; it is functional. As we face global challenges like climate change and resource scarcity, the “measure twice, cut once” adage has never been more critical. VR allows us to “build” the project virtually, identifying clashes, design flaws, and spatial awkwardness before a single shovel hits the ground. It supports the emerging trend of regenerative architecture—design that heals ecosystems—by allowing us to visualize complex environmental data and sustainable systems in a way that static diagrams cannot convey. We are moving toward a future where the digital twin is born before the physical twin, serving as a prototype for reality itself.

The Hardware Landscape: Assessing the Tools of Immersion

If software is the soul of VR, hardware is the body. The effectiveness of VR and architecture workflows depends heavily on the tools we strap to our faces. For years, the industry was bifurcated into two camps: the high-end, expensive, tethered setups that required a supercomputer to run, and the cheap, mobile headsets that offered a subpar experience. Today, that landscape has shifted dramatically, offering a spectrum of choices that cater to different phases of the design process.

1. The Battle for the Face: Standalone vs. Spatial Computing

The market is currently witnessing a fascinating divergence between “accessible VR” and premium “spatial computing.” On one side, we have devices like the Meta Quest 3 and its successors. These standalone headsets have become the workhorses of the industry. They are affordable, wireless, and “good enough” for 90% of architectural tasks. The Quest 3, for instance, offers a high-resolution display and full-color passthrough, allowing you to blend the virtual model with your physical office. This “Mixed Reality” (MR) capability means you can place a virtual architectural model on your conference table and have a team walk around it, discussing the form as if it were a physical foam core model. The barrier to entry here is low; you don’t need a render farm to run these. You can load a model and go.

On the other end of the spectrum lies the Apple Vision Pro and high-end competitors like Varjo. Apple has rebranded the experience as “spatial computing,” distancing itself from the gaming roots of VR. The difference here is pixel density and interface. The Vision Pro uses micro-OLED displays that eliminate the “screen door effect”—the visible grid of pixels that plagued early VR. For an architect, this is not just a luxury; it is a professional necessity. When you need to read the fine print on a virtual finish schedule, or when you want a client to appreciate the texture of a specific fabric, resolution matters.

The interaction paradigms also differ. The Quest relies on controllers—great for gaming and precise navigation but potentially intimidating for a non-tech-savvy client. The Apple ecosystem relies on eye-tracking and hand gestures. You look at a door handle and tap your fingers to open it. This “magical” interface removes the friction of technology, allowing the client to focus entirely on the architecture rather than the tool. However, the price point of these premium devices—often seven times that of a Quest—means they are typically reserved for high-stakes presentations and luxury residential projects where the “wow factor” translates directly to sales.

2. The Professional Grade: Varjo and Tethered Systems

For the “power users”—the large firms doing massive airports or intricate master plans—consumer headsets sometimes fall short. This is where companies like Varjo come in. Used by firms like KPF, Varjo headsets offer “human-eye resolution,” providing a level of clarity that is indistinguishable from reality. These systems are often tethered to powerful workstations. Why tether? Because real-time ray tracing—the holy grail of lighting simulation—requires the massive parallel processing power of a dedicated desktop GPU. A mobile chip in a standalone headset simply cannot calculate the millions of light bounces required to accurately simulate how sunlight will refract through a custom glass curtain wall.

3. Hardware Comparison for Architects

| Feature | Meta Quest 3 (Standalone) | Apple Vision Pro (Spatial Computer) | Varjo XR-4 (Professional Tethered) |

| Primary Use Case | Daily design review, internal coordination, accessible client VR. | High-end client presentations, luxury residential sales, mixed reality work. | Hyper-realistic visualization, ray-tracing, simulation-grade accuracy. |

| Resolution | 4K+ Infinite Display (LCD) | Micro-OLED (23 million pixels) | Human-eye resolution (Mini-LED/QLED) |

| Field of View (FOV) | ~110° Horizontal | ~100° Horizontal | ~120° Horizontal |

| Pass-through | Full color, decent quality. | High-fidelity, low latency. | Photorealistic mixed reality. |

| Controller | Physical controllers + Hand tracking. | Eye + Hand tracking only. | Controllers + Hand tracking + SteamVR. |

| Price Tier | Accessible (~$500 range) | Premium (~$3,500 range) | Enterprise (~$4,000+ range) |

| Tether Requirement | Wireless (Optional PC Link) | Wireless (Battery Pack) | Tethered to PC Workstation |

4. The Ergonomics of Immersion

We must also address the physical reality of wearing these devices. Weight and balance are critical. A client will not be impressed by your design if they have a headache from a heavy headset pressing on their sinuses after five minutes. The Vision Pro, for example, has faced criticism for its weight and the external battery pack, whereas the Quest 3 is generally lighter. However, the balance of the device matters as much as the raw weight.

Furthermore, the “passthrough” capabilities of modern headsets mitigate the isolation factor. In the early days of VR, putting on a headset meant being blind to the real world, which made many clients feel vulnerable or awkward in a public meeting. With high-quality passthrough, a client can see their architect sitting across the table and the virtual building standing next to them. This creates a safer, more social environment for collaboration.

The Software Ecosystem: Rendering Engines and Real-Time Visualization

If the hardware provides the canvas, the software provides the paint. The software landscape for VR and architecture has exploded, moving away from static rendering engines to dynamic, real-time environments that borrow heavily from the video game industry. We are witnessing a battle for the architect’s workflow, with ease of use pitting itself against graphical fidelity.

1. The Real-Time Revolution: Enscape vs. Twinmotion

For the vast majority of architects, the choice of VR software comes down to two heavyweights: Enscape and Twinmotion. Understanding the difference is key to optimizing your practice.

Enscape is the champion of the “integrated workflow.” It lives inside your BIM software (Revit, SketchUp, Rhino, Archicad) as a plugin. You do not export a file; you simply open a window. If you move a wall in Revit, it moves instantly in Enscape. This immediacy makes Enscape a design tool, not just a presentation tool. You can design with the goggles on. Its rendering quality focuses on “architectural clarity”—clean lines, decent lighting, and ease of use. It is the tool you use on a Tuesday afternoon to check a corridor width or show a colleague a detail.

Twinmotion, on the other hand, is a destination. Powered by the Unreal Engine, it is a standalone application. You sync your model to it, but once you are there, you are in a different world. Twinmotion excels at “atmosphere.” It has vast libraries of animated people, swaying trees, and dynamic weather systems. You can paint a forest, change the season from summer to winter with a slider, and populate a street with moving cars in minutes. It is the tool you use for the Friday client presentation where you need to sell the feeling of the project. The trade-off is the workflow; because it is separate, the feedback loop between design changes and visualization is slightly slower than Enscape’s instant sync.

2. The Heavyweights: Unreal Engine 5 and Unity

For those who need to push the boundaries of what is possible, “game engines” like Unreal Engine 5 (UE5) and Unity offer the ultimate sandbox. These are not just rendering tools; they are development platforms. UE5, in particular, has revolutionized the industry with technologies like “Lumen” (dynamic global illumination) and “Nanite” (virtualized geometry).

Lumen means you no longer have to “bake” lighting—a time-consuming process of pre-calculating shadows. You can move the sun, and the light bounces accurately in real-time. Nanite allows you to import massive, movie-quality 3D assets—millions of polygons—without crashing the system. This allows for a level of detail that was previously impossible in VR, from the individual threads on a sofa cushion to the rough texture of a scanned brick wall.

However, using Unreal Engine requires a skillset akin to game development. It is complex, node-based, and has a steep learning curve compared to the “plug-and-play” nature of Enscape. It is typically the domain of dedicated visualization specialists within a firm rather than the general architect.

3. The Pursuit of Photorealism: V-Ray and Corona

We cannot ignore the stalwarts of photorealism: V-Ray and Corona. While the industry is moving toward real-time, there is still a place for the absolute physical accuracy of ray tracing. When you need a “hero shot” for a brochure that is indistinguishable from a photograph, V-Ray is the king. It calculates light behavior with scientific precision, handling complex optical effects like caustics (light focusing through glass) and subsurface scattering (light glowing through marble or leaves).

The exciting development here is the bridge being built between these worlds. Chaos (the makers of V-Ray) now offers Chaos Vantage, which allows users to take a complex V-Ray scene and explore it in real-time ray tracing using the power of modern GPUs. This hybrid workflow allows firms to keep their high-fidelity assets while gaining the speed of interactive walkthroughs.

4. Cloud Rendering and the “Thin Client” Future

A major bottleneck for VR is hardware requirements. Not every client has a $5,000 workstation. This is where Cloud Rendering and “Pixel Streaming” come into play. Services like Vibe3D or specialized cloud platforms allow the heavy rendering to happen on a remote supercomputer. The visual stream is then beamed to the client’s iPad, laptop, or lightweight VR headset over the internet. This democratizes high-end VR, allowing an architect to show a photorealistic Unreal Engine model to a client on a construction site using just a tablet. As 5G and internet speeds improve, this “thin client” approach may eventually render the expensive office workstation obsolete.

Generative AI and the Future of Modeling

While VR and architecture change how we see design, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is changing how we create the content we see. We are witnessing the birth of a new workflow where the architect acts less like a digital bricklayer and more like a director, guiding AI agents to populate and texture the virtual world.

1. Text-to-3D: The End of Empty Worlds

One of the biggest challenges in creating convincing VR environments is filling them. A room looks sterile without furniture, books, plants, and lamps. Modeling these items manually is tedious. Enter Text-to-3D generative AI. Tools like Point-E, Shap-E, and newer commercial iterations allow designers to simply type prompts like “a worn leather chesterfield sofa, mid-century modern style” or “a rustic oak coffee table,” and the AI generates a unique 3D model.

While the topology of these AI-generated models is still evolving (sometimes they can be a bit “blobby” or unoptimized), the pace of improvement is blistering. We are rapidly approaching a point where architects can populate an entire virtual hotel lobby with unique, custom-designed furniture simply by describing it. This not only saves time but creates a “lived-in” feel that enhances the sense of presence in VR.

2. Skybox AI: Context on Demand

Nothing breaks immersion faster than a black void outside a virtual window. Traditionally, architects had to scour libraries for high-resolution 360-degree photos (HDRI maps) that matched their site conditions. Now, tools like Blockade Labs’ Skybox AI allow you to generate custom 360-degree environments from a text prompt.

Need a view of a “foggy London street at dawn with Victorian architecture”? Or perhaps a “Martian landscape with a terraformed biodome in the distance”? Skybox AI creates these seamless panoramic images in seconds. You can then wrap this image around your virtual model, providing perfect ambient lighting and context. This is invaluable for conceptual design where the specific site might not yet be chosen, or for creating “mood” options for clients (e.g., showing the same house in a snowy winter forest and a sunny beachside setting).

3. From 2D to 3D: Depth Maps and Concept Art

Architects love sketches. But turning a sketch or a mood board image into a 3D space usually involves starting from scratch. AI is bridging this gap. Workflows using tools like Midjourney or Stable Diffusion can generate stunning architectural concept art. Then, using “Depth Map” estimation AI (like MiDaS or ControlNet), we can extract 3D depth information from that 2D image. This data can be displaced into a rough 3D mesh, effectively “inflating” the painting into a 3D space you can step into.

This allows for a radical new workflow: “Sketch to VR” in minutes. An architect can generate ten different variations of a lobby in Midjourney, turn the best one into a rough 3D mesh using depth mapping, and put a client in it to test the “vibe” before drawing a single precise line in Revit. It shifts the focus from “modeling” to “curating” in the early design phases.

The Psychology of Virtual Space: Perception and Human Factors

When we put a client in a VR headset, we are not just showing them a picture; we are hacking their sensory system. Understanding the psychology and physiology of this experience is crucial. If you ignore the human factor, you risk not just a failed presentation, but a physically ill client.

1. Spatial Perception and Cognitive Load

Research in VR and architecture shows that people perceive space differently in VR than they do on paper or even on a screen. On a floor plan, a 3-foot wide hallway looks fine. In VR, the user’s proprioception (sense of body position) kicks in, and they might immediately feel the space is “claustrophobic.” Studies confirm that spatial perception in VR is highly correlated with real-world perception, much more so than any other medium. This makes VR the ultimate validation tool. We can test sightlines, ceiling heights, and ergonomic reaches (e.g., in a hospital room or kitchen) with high fidelity.

However, virtual environments can also induce cognitive overload. A hyper-realistic model with too much visual noise—patterned wallpapers, complex textures, moving crowds—can be overwhelming. The brain struggles to process the artificial stimuli. Expert VR practitioners often use “stylized” or “clay” rendering modes for early design discussions to keep the client focused on the form and flow of the space, rather than getting distracted by the grain of the wood floor.

2. The Motion Sickness Problem

The “Achilles’ heel” of VR is cybersickness. This happens when there is a mismatch between the visual system (your eyes see you moving) and the vestibular system (your inner ear feels you are sitting still). This sensory conflict causes nausea. For an architect, making a client sick is a disaster.

To mitigate this, you must adhere to strict best practices:

- Frame Rate is King: You must maintain a stable 90 frames per second (FPS). If the visuals stutter or lag (judder), the brain detects the glitch, and nausea sets in immediately. This is why optimizing your model geometry is not optional.

- Locomotion Choices: “Teleportation” (pointing and clicking to jump to a new spot) is much more comfortable for most people than “smooth locomotion” (gliding like a ghost using a joystick). Smooth movement creates a strong vestibular disconnect.

- Vignetting: Many VR tools now offer “comfort modes” that narrow the field of view (creating a tunnel vision effect) when the user moves. This reduces the amount of motion perceived by the peripheral vision, which is highly sensitive to movement and a primary trigger for sickness.

- Sit Down: Encouraging clients to sit in a swivel chair while experiencing VR can ground them and reduce the feeling of imbalance.

3. Lighting and Acoustic Simulation

Perception isn’t just visual. “Auralization” is the process of simulating the acoustic properties of a space in VR. Using ray-tracing for sound, we can let a client hear how a lecture hall will sound with concrete walls versus acoustic panels. This multisensory approach is vital for designing performance spaces, classrooms, or busy offices.

Similarly, VR is revolutionizing daylight analysis. Instead of looking at a false-color heat map that says “500 lux,” a client can stand in the virtual room at different times of day. They can physically experience the glare on their monitor or the gloom in a deep corner. This qualitative assessment of light is often more meaningful for design decisions than quantitative data alone.

Integrating VR into the Architectural Workflow

So, how do we actually weave this into the daily grind of an architecture firm? It requires a shift from viewing VR as a “final deliverable” to viewing it as a “process tool.”

1. The “Live” Design Session

The most powerful workflow is the “Live Sync” session. Picture this: The project architect is wearing a headset, walking through the BIM model. The rest of the team—designers, engineers, the client—is watching a large screen showing the VR view. The architect spots a conflict: a beam is too low.

In the old world, this would be a note, a sketch, a CAD revision, and a meeting next week. In the VR workflow, the BIM operator sitting at the computer adjusts the beam height in Revit. The change happens instantly in the architect’s headset. “A little higher… okay, that feels right.” The decision is made, modeled, and approved in seconds. This collaborative, real-time problem solving is where VR and architecture truly shine, reducing RFI cycles and saving weeks of coordination time.

2. Multi-User Collaboration: The “Metaverse” of Construction

The solitude of the single headset is ending. Platforms like The Wild, Arkio, or collaborative modes in Twinmotion allow multiple users to inhabit the same virtual model simultaneously, regardless of their physical location. The lead architect is in London, the structural engineer in New York, and the client in Dubai. They all meet in the virtual lobby of the project. They appear as avatars. They can point at things, sketch in 3D space, and even scale the model down to “dollhouse” size to stand around it like a table. This reduces travel costs and improves communication, as everyone is literally “on the same page”—or rather, in the same room.

3. From Design to Construction Site

VR is also moving to the job site. Contractors are using VR and AR (Augmented Reality) to visualize complex assemblies before installation. By overlaying the BIM model onto the physical site (using AR glasses or tablets), workers can see exactly where the ductwork should run or where the penetrations in the slab need to be. This “digital rehearsal” reduces rework and ensures that the design intent is executed faithfully.

The Business of VR: Fees, Marketing, and ROI

Let’s talk money. Implementing VR requires investment in hardware, software, and training. How do firms recoup this cost?

1. Monetization Strategies

There are three main ways architects are charging for VR and architecture services:

- The “Value Add” Model: Many firms absorb the cost of basic VR (like Enscape walkthroughs) into their standard design fee. They view it as a tool that speeds up approval and reduces their own risk of errors. It’s a loss leader that wins the project and saves money on the back end by preventing mistakes.

- The “Menu” Model: For high-fidelity, curated VR experiences (e.g., a polished interactive tour for a fundraising gala or a condo sales center), firms charge a separate line item. These fees can range from $5,000 to $20,000 or more, depending on the complexity, interactivity (e.g., changing finishes), and duration of the experience.

- The “Marketing Package”: Architects partner with developers to provide a suite of marketing assets—renderings, animations, and VR tours. This is often priced as a percentage of the project’s marketing budget rather than an hourly architectural fee. A high-end cinematic VR walkthrough can command fees upwards of $50,000 if it involves complex storytelling and custom assets.

2. Marketing ROI: Winning the Job

Beyond direct fees, the ROI of VR comes from winning work. In a competitive interview, the firm that puts the selection committee inside the proposed building has a massive psychological advantage over the firm that just shows slides. The emotional connection forged in VR is “sticky.” Clients remember how they felt in the space. Real estate statistics show that VR tours can increase buyer interest and reduce the time a property sits on the market, which is a compelling argument for developer clients.

3. Tax Incentives: Section 179

For firms in the United States, the government essentially subsidizes the move to VR through Section 179 of the IRS tax code. This provision allows businesses to deduct the full purchase price of qualifying equipment and software in the year it is placed in service, rather than depreciating it over several years.

For the current tax environment, the deduction limit is substantial (up to $2,500,000 in some projections for coming years), with a spending cap before phase-out begins. This applies to:

- High-end workstations (rendering computers).

- VR Headsets (Quest, Varjo, Vision Pro).

- Off-the-shelf software (Revit, Enscape, V-Ray licenses).

This immediate tax relief significantly lowers the barrier to entry, allowing firms to upgrade their tech stack with pre-tax dollars.

Beyond Visualization: Digital Twins, Heritage, and Technical Simulation

The power of VR extends far beyond just “seeing” a new building. It is becoming a tool for managing the lifecycle of the built environment and preserving our cultural history.

1. The Digital Twin: Architecture as an Operating System

A Digital Twin is a virtual replica of a physical building that is connected to real-time data. Imagine a facility manager wearing a VR headset. As they look at a pump in the mechanical room, the virtual overlay shows them its live operating temperature, vibration stats, and maintenance history. They can “see” through walls to trace a leaking pipe.

VR serves as the interface for this data. It allows for “predictive maintenance”—simulating scenarios to see how the building will perform. “What happens if the occupancy doubles?” “What if the AC fails in this zone?” The Digital Twin allows owners to test these scenarios in the virtual safety of VR before they happen in reality.

2. Heritage Conservation: The Digital Ark

Our built heritage is fragile. Wars, climate change, and time threaten historical sites. VR is becoming a “Digital Ark.” Through laser scanning and photogrammetry, we can create millimeter-accurate copies of existing structures.

Take the case of the Rovigo city walls in Italy. Researchers combined aerial photogrammetry and laser scanning to create a high-precision 3D model. They then used VR to allow users to not just see the walls as they are today, but to toggle through time—seeing them as medieval fortifications, then as 19th-century ruins, and finally as modern integrated structures.

Similarly, VR allows access to sites that are too fragile for tourism, such as the Chauvet-Pont-D’Arc cave in France (with its paleolithic art) or ancient Egyptian tombs. VR provides a way to democratize access to these cultural treasures without loving them to death.

3. Technical Simulation: Acoustics and Safety

VR is also a safety lab. Fire safety engineers use VR to simulate evacuations. They can fill a virtual building with smoke and see if people (avatars or real test subjects) can find the exits. This reveals signage blind spots that a code analysis might miss.

In acoustics, researchers are using VR to test speech intelligibility in classrooms. By simulating the acoustic environment, they can verify if a student in the back row will be able to hear the teacher clearly, long before the acoustic panels are ordered.

Conclusion

We stand at the threshold of a new era in architecture. The integration of VR and architecture is not a trend; it is a trajectory. We are moving from a profession of static images to one of dynamic experiences. The tools we have discussed—from the accessible Quest 3 to the powerhouse Unreal Engine, from the generative magic of AI to the precision of Section 179 tax planning—are the bricks and mortar of this new practice.

For the architect, the message is clear: do not fear the headset. Embrace it. It is the ultimate empathy machine. It allows you to see your work through your client’s eyes, to feel the space before it is built, and to communicate with a clarity that was previously impossible. The “virtual” is no longer the opposite of the “real.” In the modern built environment, the virtual is the blueprint for the real. It is the testing ground, the sales floor, and the archive.

As we look to the future, the line between the physical and the digital will continue to blur. The architects who master this hybrid reality—who can weave together the data of a Digital Twin with the poetry of a well-proportioned room—will be the ones who define the skylines of tomorrow. So, put on the goggles. Step inside. The future is waiting to be built.